Multiple Myeloma: Rapidly Advancing Therapeutic Landscape

By Xcenda

HTA QUARTERLY | WINTER 2017

Multiple Myeloma: A rapidly advancing therapeutic landscape

By Kristen Migliaccio-Walle and Clémence Arvin-Berod, PharmD

In the last decade, advancements in genomics have increased the understanding of disease biology, cellular mechanisms, and pathogenesis, which has led to tremendous improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of MM.

Therapies and the complexity to treat MM

HTA recommendations of MM therapies

In Europe, Velcade (bortezomib) was assessed by the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS) in France in 2004 for the treatment of patients who received at least 2 prior treatments and was awarded a medical benefit rating (SMR) of “important” and a level II (important) added medical benefit rating (ASMR). Velcade was reassessed in 2006, 2007, 2009, and, most recently, in 2014 to become approved for use as a first-line agent to treat patients with MM in combination with dexamethasone and/or thalidomide. The SMR has consistently been rated, and remains, as “important” and the ASMR is currently rated “moderate” (level III). Velcade is considered the initial treatment of choice by physicians and the reference treatment for first-line therapy in France for patients with MM aged less than 65 years.

In the United Kingdom (UK), Velcade was considered to be a cost-effective treatment option by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2007 for patients with MM who have experienced their first relapse after having received 1 prior therapy and who have undergone, or are unsuitable for, bone marrow transplantation. The basis for this decision was an estimated incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £20,700 per QALY gained. As in France, Velcade was reassessed in 2014 in the UK. As a result, Velcade was considered to be cost-effective (ICER below the £30,000 per QALY threshold) as induction treatment for previously untreated patients eligible for chemotherapy.

The Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) did not recommend Velcade in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in July 2009 to treat patients with progressive MM; although the combination significantly increased the time to disease progression compared to Velcade alone, the submission did not present an adequately robust economic evaluation. However, Velcade was approved to treat progressive MM in October of the same year. In 2012, following an abbreviated submission, Velcade was approved to treat previously untreated MM patients in combination with melphalan and prednisolone and alone to treat patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy. This indication was subsequently restricted in 2014 for use as a triple therapy in combination with dexamethasone and thalidomide for the induction treatment of adult patients with previously untreated MM.

In Germany, there has been no assessment of Velcade by the Institut fur Qualitat und Wirtschaftlichkeit (IQWiG), as the therapy was launched before the initiation of the Act on the Reform of the Market for Medical Products (Arzneimittelmarkt-Neuordnungsgesetz, AMNOG) process that was implemented in 2011.

Ninlaro (ixazomib) did not receive approval by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and therefore was not evaluated by regional health authorities in Europe. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2015 and was recently evaluated by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review in the US (see below).

Empliciti (elotuzumab) was just granted regulatory approval from the EMA in 2016. It has been proposed for assessment by NICE (but was not submitted to SMC) for treating previously untreated MM. In Germany, IQWiG concluded that the added benefit of the therapy in comparison to lenalidomide and dexamethasone was not proven. The only study submitted, ELOQUENT-2, failed to convince German payers on the grounds of inappropriate comparator dosage.

Impact of Orphan Drug Designation in Europe

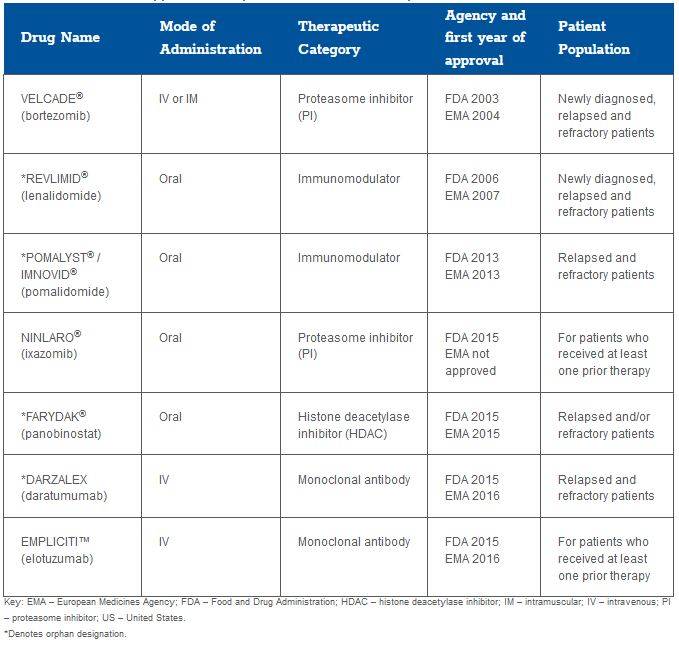

Several therapies have been granted orphan drug status by the FDA and EMA for the treatment of relapsed and refractory MM (Table 1); the effect of this designation on HTA recommendations has, to date, varied substantially across regional markets. Darzalex was recently approved by the FDA and EMA and has not yet been reviewed by HTA authorities in Europe.

In 2007, Revlimid (lenalidomide) was approved for use in France by HAS in combination with dexamethasone for patients who received at least 1 prior therapy. The SMR was considered important and the ASMR was moderate (level III), and although it was not compared to Velcade directly, it was considered with similar added medical benefits to patients with MM. It was reassessed in France in 2012, but no change resulted and Revlimid maintained its reimbursement status in the French market.

In the UK, Revlimid was first approved in 2009 by NICE and the technology appraisal was revised in 2014. It is licensed for use with dexamethasone in patients who received 2 or more therapies. The ICER in this patient population was £24,584 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. In 2008, the SMC first advised against the use of lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone for patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy despite concluding that it increased the time to disease progression compared to dexamethasone alone in MM. SMC based this initial guidance on the determination that the manufacturer “did not present a sufficiently robust case” nor did it sufficiently justify the cost of treatment relative to the anticipated health benefits. Following a resubmission in 2010, Revlimid was accepted for use in Scotland with the restriction of use as a third-line option and in combination with dexamethasone. More recently, in 2014, the manufacturer made a second resubmission, securing the use of Revlimid at first relapse in patients who have received prior therapy with bortezomib.

In Germany, there has been no IQWiG assessment of Revlimid (lenalidomide), as the therapy was launched before the initiation of the AMNOG process in 2011.

In the UK, Imnovid® (pomalidomide) was assessed by NICE in 2015 but was not recommended because the ICER submitted by the manufacturer was considered too high (over £50,000 per QALY gained against bortezomib). On the clinical assessment, progression-free survival (PFS) and OS were the key clinical evaluation criteria along with unmet need, end of life, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Access to Imnovid for patients in the UK was subsequently provided through funding by the Cancer Drug Fund (CDF). In a reversal of the 2015 evaluation, Imnovid was recently recommended by NICE for “routine use” in England and Wales based on new data submitted in 2016. In 2014, the SMC recommended against the use of Imnovid as it considered that the economic analysis and the cost/benefit ratio were not sufficient to be recommended in Scotland. In that same year, the manufacturer resubmitted a dossier including a patient access scheme that significantly improved the cost-effectiveness of the therapy. Imnovid was subsequently approved by the SMC, as the medicine significantly increased PFS compared to high dose dexamethasone.

In France, Pomalyst first gained access through the ATU (Autorisation Temporaire d’Utilisation - temporary authorization of use) between 2012 and 2013. In January 2014, it was approved by HAS with an SMR rating of “substantial” and with a moderate improvement of the ASMR.

In Germany, Pomalyst has not been assessed by IQWiG. Due to its orphan designation by the EMA, an improved medical benefit is assumed. On this basis, the Gemeinsamer Bundsausschuss (G-BA) approved Pomalyst for use in Germany in early 2014. The so-called “orphan-drug loophole” applies only to products that do not exceed a sales threshold of €50 million in Germany. As Pomalyst revenue subsequently exceeded this threshold, the manufacturer was required to submit a dossier in 2015 defending the added medical benefit of the product to the German HTA agency. G-BA concluded that there was indication of a considerable therapeutic benefit for patients who were taking high-dose dexamethasone as monotherapy. No additional benefit was determined, however, for patients in whom high-dose dexamethasone was part of a multi-drug regimen.

Farydak (panobinostat) was granted an ATU in France in 2015 based on 1 randomized controlled trial against placebo. The opinion of the transparency committee was released in April 2016, granting a moderate SMR but no ASMR (level V) due to an important toxicity observed during the clinical trials, resulting in Farydak becoming one of the last treatment options (eg, third line-plus) for patients with MM.

For NICE in the UK, Farydak was recommended as a cost-effective treatment option in 2016 for relapsed patients who received at least 2 prior regimens, with an ICER estimated to be less than £25,000 per QALY gained. Farydak is considered an additional treatment option in third line and does not significantly change the sequence of care for patients. In Scotland, Farydak was considered under the end of life and orphan process this year. The SMC recommended Farydak in combination with Velcade and dexamethasone for adult patients with relapsed and/or refractory MM who have received at least 2 prior regimens.

In Germany, Farydak is subject to the same pathway as Pomalyst, as it also has an orphan indication in MM. Therefore the G-BA approved panobinostat for use in Germany with the standard “non-quantifiable” added benefit. It is too early to determine if revenue will exceed the specified threshold and require the manufacturer to subsequently submit a dossier.

Darzalex (daratumumab) was just granted regulatory approval from the EMA in 2016, which explains why it has not yet been widely reviewed by EU HTA agencies. A recent submission to the SMC did not recommend the use of Darzalex by the NHS Scotland, citing insufficient evidence to support the costs relative to the benefits.

Value Assessment in the US

In the US, there are no formal HTA bodies as there are in Europe. Nevertheless, technology assessment by independent groups striving to systematize how we value new health interventions has rapidly emerged over the last 18 months in the form of value assessment frameworks. In particular, treatment options for MM have been evaluated within the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Value Framework, the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Drug Abacus, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Evidence Blocks™ and by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Primary therapies of interest have included:

- Kyprolis® (Carfilzomib)

- Darzalex® (Daratumumab)

- Empliciti® (Elotuzumab)

- Ninlaro® (Ixazomib)

- Farydak® (Panobinostat)

- Pomalyst® (Pomalidomide)

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review evaluated the comparative clinical effectiveness of each product in the context of its approved treatment regimen by line of therapy (second line and third line separately). Evidence on OS and PFS were reported for all regimens; however, final OS results were reported for only 2 regimens (Farydak, Pomalyst). Thus, with results still pending and emerging, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review concluded that data were insufficient to distinguish clinical benefit among the newer regimens. Evidence on HRQoL outcomes was limited to 4 of the 6 regimens (Kyprolis, Pomalyst, Empliciti, and Ninlaro). Overall, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review concluded that given the lack of head-to-head data, there was insufficient evidence to distinguish comparative net health benefit between newer regimens.

The current NCCN Guidelines and Evidence Blocks™ for MM recommend the use of Velcade and/or Revlimid as components of a combination regimen as the preferred primary therapies of choice for patients with MM. Preferred regimens for patients previously treated for MM are greater in number and receive strong evidence ratings (category 1) for specific regimens, which include Kyprolis, Darzalex, Empliciti, Ninlaro, and Pomalyst/Imnovid in combination with dexamethasone and, often, Velcade or Revlimid.

The ASCO net health benefit (NHB) of these newer regimens for the treatment of relapsed or refractory MM has not been published. An independent evaluation of the evidence to inform the ASCO framework considered the impact on the components of the NHB score (ie, clinical benefit, toxicity). The ASCO value framework prioritizes a hierarchy of clinical benefit measures starting from OS to PFS and response rate (RR). When the impact of each available measure was compared, there was a notable lack of consistency in the clinical benefit points estimated for each product across outcome measures.

The Drug Abacus includes Farydak, Pomalyst, and Velcade in the current calculator and the resulting “Abacus price” is highly dependent on the user’s specified willingness-to-pay threshold. Analyses over a range of potential assumptions indicated a favorable Abacus price in a majority of scenarios for Velcade and approximately half of Farydak and Pomalyst scenarios.

Implications and Recommendations for Manufacturers

The quickly evolving oncology treatment landscape and rapid emergence of novel therapies to address unmet needs in MM, combined with increasing requirements to demonstrate incremental value, have resulted in often opposing challenges for health authorities and manufacturers alike. In this setting, optimal evidentiary requirements for decision making frequently must be balanced with timely and expeditious patient access to promising therapies. There are a few considerations that may be given as we continue to balance these needs:

- Design clinical trials and choose comparators such that they satisfy both regulatory filing requirements (eg, EMA, FDA) and the evidentiary needs of European HTA agencies and/or US value frameworks (eg, head-to-head trials, inclusion of HRQoL)

- There is a need to better understand and quantify the factors that drive value across the range of therapeutic options and promising new alternatives in patients with MM (importantly, the various combinations and sequences)

- To optimally address the therapeutic goals of patients, it is critical to understand what they value in treatment and outcomes.

- For example, in the UK, a grant was made available by NICE to a patient group Myeloma UK in order to explore methodologic considerations when it comes to patient health preferences. The study is expected to last 2 years and aims at quantitatively capturing patients’ preferences to be incorporated into HTA decision modeling

- It will continue to be important for treatment guidelines to keep pace with the evolution in therapeutic alternatives and diagnostics to guide best clinical practices and support coverage and reimbursement

- Finally, in this new era of value-driven decision making, the randomized clinical trials required for product approval have been transformed from the end goal of a development program to being an intermediate point in the ongoing course of value demonstration

- In Germany, for example, the impact of orphan drug status is high, although the revenue threshold can oblige the manufacturer to submit additional evidence in a dossier after the first year of launch

- This was also demonstrated in the recent reversal of the decision by NICE on the use of pomalidomide in England and Wales

The article should be referenced as follows:

Migliaccio-Walle K, Arvin-Berod C. Multiple myeloma: A rapidly advancing therapeutic landscape. HTA Quarterly. Winter 2017. Jan. 19, 2017.

References:

-

ALD 30 Myélome Multiple, Haute Autorité de Santé. December 2010

-

Bortezomib NICE Technology Appraisal guidance TA 129, 2007

-

Bortezomib NICE Technology Apraisal guidance TA 311, 2014

-

Bortezomib Avis de la Commission de la Transparence, Janvier 2014

-

Cornell RF, Kassim AA. Evolving paradigms in treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma:increased options and increased complexity. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(4):479–491.

-

Elotuzumab in multiple myeloma: added benefit not proven, Press Release IQWiG, September 2016

-

ESMO guidelines Multiple Myeloma

-

Ferlay J, Bray F, Sankila R, Parkin DM. EUCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence in the European Union 1998, version 5.0. IARC CancerBase No.4. Lyon: IARCPress; 1999

-

Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Treatment Options for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Effectiveness, Value, and Value-Based Price Benchmarks Final Evidence Report and Meeting Summary June 9, 2016 https://icer-review.org/material/mm-final-report/

-

Lenalidomide NICE Technology Appraisal guidance, TA 171 June 2009

-

Lenalidomide Avis de la Commission de la Transparence HAS, October 2007

-

Multiple Myeloma, Diseases and Conditions, Mayo Clinic

-

Myeloma, Diagnosis and management, NICE Clinical Guidance Feb 2016

-

Multiple Myeloma, American Cancer Society

-

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Evidence Blocks™ Multiple Myeloma Version 3.2016. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/evidenceblocks/ [Accessed August 15, 2016].

-

Panobistat NICE Technology Appraisal guidance, TA 380 2016

-

Panobistat Avis de la Comission de Transparence Avril 2016

-

Pomalidomide NICE Technology Appraisal guidance, TA 338 March 2015

-

Rajan AM, Kumar S. New investigational drugs with single-agent activity in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer Journal. 2016;6.

-

Refusal of the marketing authorization for Ninlaro (ixazomib) EMA June 2016

-

Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: A Conceptual Framework to Assess the Value of Cancer Treatment Options. JCO 2015;33(23):2563-2578.

-

SMC Advice 927/13 Bortezomib December 2013

-

SMC Advice 822/12 Bortezomib November 2012

-

SMC Advice 302/06 Bortezomib October 2009

-

SMC Advice 441/08 Lenalidomide Resubmission March 2014

-

SMC Advice 441/08 Lenalidomide Resubmission April 2010

-

SMC Advice 441/08 Lenalidomide April 2008

-

SMC Advice 1122/16 Panobinostat January 2016

-

SMC Advice 503/08 Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin June 2009

-

SMC Advice 972/14 Pomalidomide Resubmission November 2014

-

SMC Advice 972/14 Pomalidomide June 2014

-

Zhou Y, Barlogie B, Shaughessy JD Jr. The molecular characterization and clinical management of multiple myeloma in the post-genome era. Leukemia. 2009;23:1941-1956