Regulatory and Market Access Impact in Europe of the Recent Medical Software Makers Guidance

By Xcenda

HTA QUARTERLY | SUMMER 2020

Regulatory and Market Access Impact in Europe of the Recent Medical Software Makers Guidance

By: Oyinkan Solanke, MSc; Jo Watts-James, MBA; Ken Redekop, PhD; Fred Sorenson, MSc | Updated May 1, 2020

As the role of technology in healthcare becomes increasingly important, and demand for new/innovative digital health technologies (DHTs) grows, understanding how the European Union’s new guidance on medical devices may affect the time to market and uptake of DHTs is essential. Equally important is the need for a better understanding of how the medical device software (MDSW) classification in the recent Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) guidance may impact the use of DHTs in Europe.

Introduction

In 2017, the European Union (EU) announced new regulations for medical devices that set out the legal and marketing authorization framework in Europe. In the MDR, the new roles and duties of regulatory bodies, including the European Medicines Agency (EMA) were issued, and a complete roadmap for the marketing authorization of medical devices was outlined. According to the EU Commission, the aim of the MDR was to “establish a modernized and more robust EU legislative framework to ensure better protection of public health and patient safety…[to] boost confidence in our medical devices industry.”

It

was planned that the MDR would come into full effect this month (May 2020); but,

due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU Commission announced on 25 March 2020 that

it is working on a proposal to postpone its introduction by one year (May 2021).

In

October 2019, seven months before the initially planned full implementation of

the MDR, the European Commission’s MDCG published guidance for manufacturers for

MDSW and delineated the criteria for its eligibility and marketing

authorization under the MDR. Specifically, the guidance document outlines

details on the qualification (what type of software is subject to the

regulations) and classification (associated device risk category) of medical

device software.

This article provides a summary of the MDCG guidance for manufacturers of medical devices and healthcare providers interested in leveraging digital innovations. It also considers some challenges the MDR may pose on the appraisal of DHTs in Europe, not only for manufacturers, but for payers and end users of these products.

Summary of MDCG guidelines

As stated above, the purpose of the MDCG guidance is to clearly define what medical software falls within the scope of the new MDR. The definition of medical device software is summarized below.

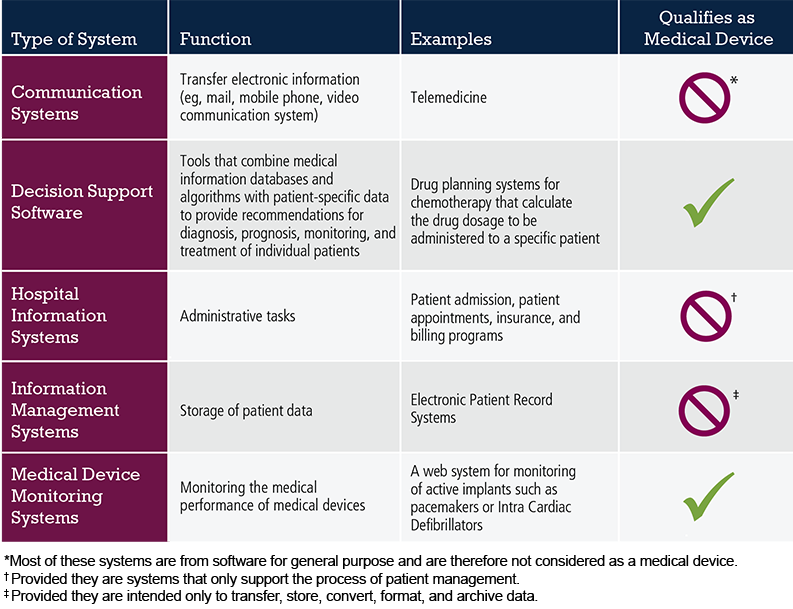

The general guiding principle to be applied in determining whether a software product is a medical device is: Does it in some way alter the course of treatment or the health outcome? If so, then yes, it is a medical device. The table below gives examples of software systems commonly seen in healthcare and whether they qualify as medical devices. As software for a medical purpose is rapidly evolving, regular updates of further examples of MDSW which are applicable within the MDR will be published in the MDCG guidance.

Table 1. Examples of Software Systems Used in Healthcare

HTA Frameworks for Digital Health in Europe

As the technology giants such as Google, Apple, and Microsoft steadily increase their presence in the healthcare space, adding to the contributions of more established companies, such as IBM and Siemens, the types of DHTs can be expected to continue to grow exponentially and become an integral part of healthcare. While the MDCG provides guidance on how MDSW and, thus, DHTs are classified and assessed for marketing authorization in the EU, the framework for assessing the value and economic impact of these technologies for European patients, healthcare systems, and payers remains less formulated.

The MDR clearly defines the regulatory criteria for marketing authorization of medical devices in Europe; however, the HTA framework for conducting the economic evaluations of DHT remains less defined. While HTA agencies such as HAS in France have developed guidelines on assessing the quality and reliability of DHT data and guidelines exist on the reimbursement requirements for medical devices in Germany and UK, the HTA landscape for digital health across Europe is still in its infancy.

Evidence Requirement Challenges for Market Access in Europe

HTA agencies play a significant role in the assessment, access, and financing decisions of new healthcare interventions and their assessment frameworks often extend beyond the efficacy and safety criteria of regulatory authorities. For EU HTA bodies and payers, new health interventions are typically evaluated based on comparative clinical efficacy, safety, and economic value relative to existing interventions and, in some cases, the provision of integrated healthcare. Thus, the assessment of new and complex DHTs poses some unique challenges, including:

- How should the outcomes data be collected and analyzed?

- What risks need to be monitored and effectively managed?

- What are the evidence generation requirements that should be used to inform pricing and resource allocation decisions that ultimately determine patient access?

For HTA agencies and payers, how health outcomes are collected and validated will be among the points of focus since the use of DHTs creates unique evidence generation challenges due to the varied nature in how data are captured, analyzed, and reported. The development of algorithms by non-medically trained personnel for use as medical device software introduces several hurdles for HTAs in their evaluations of DHTs. Particularly, regarding the validity of the algorithms, reliability of the underlying data, and transparency around the software or coding itself. Additionally, as the demand for real-world evidence in healthcare decision making rises, manufacturers of DHTs may also be faced with the “operational, technical, and methodological challenges” associated with using real-world data (RWD). Key challenges include data privacy and access to data collected by DHTs as well as how to validate RWD used in economic evaluations.

Personalized Medicine and the Patient Perspective

While the use of DHTs may pose some challenges to HTA frameworks, their contribution and potential in healthcare are undeniable. Their impact is evident in nearly every area of our healthcare system and most especially in the area of personalized care. DHTs lend themselves perfectly to the increasing demand for personalized medicine—personalized medicine refers to “a medical model using characterization of individuals' phenotypes and genotypes (eg, molecular profiling, medical imaging, lifestyle data) for tailoring the right therapeutic strategy for the right person at the right time, and/or to determine the predisposition to disease and/or to deliver timely and targeted prevention.” DHTs further facilitate the capturing of individual level health information as the end-users are more often patients and their caregivers.

Additionally, DHTs create an avenue to include the patient voice in the evaluation of new health interventions and could enhance the HTA process. Some HTA agencies adopt the patient perspective in their evaluation and for these agencies, DHTs contribute to the already complex array of means by which patient data may be captured and, as such, the validity of patient reported data needs to be considered. For instance, DHTs may provide more accessible user interfaces for patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and potentially improve the quality (and quantity) of PRO data being collected. However, this raises new challenges as to the adaptation and validation of PRO data collected from DHTs and how to consistently assess the comparative value. This may happen in instances where competing DHTs are developed for the same purpose and if health outcomes are inconsistently captured across DHTs or not systematically validated.

Conclusion

As pressures to contain rising costs in healthcare mounts, there is an increasing and continuous need to demonstrate value of both existing and new health interventions including DHTs. While digital health offers considerable potential in transforming health and healthcare systems across the world to be more patient-centric, it raises new challenges on how HTA agencies can effectively and comprehensively appraise these technologies. Although there are some early initiatives to structure the HTA of DHTs in a few European countries, the majority of countries throughout Europe are paying little attention to frameworks for reimbursement and market access. Understanding how the MDR and MDCG will shape marketing authorization is essential for manufacturers of DHTs and careful preparation will be critical to address the challenges to reimbursement.

The article should be referenced as follows:

Solanke O, Watts-James J, Redekop K, Sorenson F. Regulatory and market access impact in Europe of the recent medical software makers guidance. HTA Quarterly. Summer 2020. https://www.xcenda.com/insights/htaq-summer-2020-eu-new-software-guidance.

Sources

- Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2019 Teil 1, Nr. 49, ausgegeben zu Bonn am 18. December 2019.

- EU Commission website. https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/medical-devices_en.

- General EU Commission Secretariat of the Council to Delegations; Document number 15054/15: Personalised medicine for patients – Council conclusions (7 December 2015). http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15054-2015-INIT/en/pdf.

- Kristensen FB, Lampe K, Wild C, Cerbo M, Goettsch W, Becla L. The HTA Core Model®—10 years of developing an international framework to share multidimensional value assessment. Value in Health. 2017;20(2):244-250.

- MDCG 2019-11: Guidance on Qualification and Classification of Software in Regulation (EU) 2017/745 – MDR and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 – IVDR.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies. 2019. Official Journal of the European Union, C 421, 17 December 2015.